Securing Medical Devices: Cyber Threats, SBOMs, and FDA Premarket Readiness

How Medical Devices Can Comply with Section 524B to Meet FDA Cybersecurity Requirements

September 17, 2025

Medical device manufacturers must now ensure every device—whether it’s a new AI‑enabled implant or a decades‑old imaging system—is resilient against constantly evolving cyber threats.

Most people picture MRI machines or pacemakers when considering medical devices, and often assume these run on proprietary software. In reality, about 96% of medical device software leverages open source, creating a complex blend of proprietary and open source components.

With stricter laws, like section 524B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), security is now expected from the design phase. It’s never been more critical to answer the question: “What’s inside your device’s software?”

After years of work in software transparency, provenance, and SBOMs, I’ve seen regulatory demands intensify across a number of industries. Let’s explore what’s become essential for quality, risk, and regulatory teams in medtech cybersecurity.

Software is Everywhere—Even in “Hardware” Devices

Software now lies at the heart of medical devices previously considered pure hardware. Today’s medical devices are sophisticated, software-driven machines.

From MRI machines and pacemakers to surgical robots and monitoring apps, nearly all rely on a blend of proprietary and open source software.

Patient outcomes depend on these devices’ software — and any vulnerability or malfunction carries immediate, serious consequences. Regulators are right to pay close attention.

Growing Scrutiny Amid Growing Threats

Recent events have proven a sobering truth: cybersecurity is patient safety. Consider these incidents:

- April 2021: A ransomware attack on a major medical device manufacturer delayed radiation therapy for cancer patients at 40 U.S. hospitals, stalling treatment for days and even weeks in some cases.

- February 2023: Three separate events disrupted medical device makers within two weeks, threatening manufacturing operations and the supply of important devices to hospitals.

- Ongoing: Healthcare systems continue to face frequent and severe cyberattacks, endangering both hospital networks and the devices connected to them.

In healthcare, cyber risks are not just about data or financial losses. They translate directly to delayed surgery, disrupted care, and lives at stake. Recognizing these risks, the FDA is sharply increasing its focus on medical device cybersecurity.

The Regulatory Landscape: Why SBOMs Are No Longer Optional

For software quality, compliance, and regulatory teams, the message is clear: software bills of materials (SBOMs) are now a required starting point for cybersecurity.

Let’s talk specifics.

The FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) has been focused on cybersecurity in medical devices for years, but new elements are coming forward.

1. New SBOM Requirements in Premarket Submissions

As of March 2023, the FDA mandates cybersecurity documentation with premarket submissions—chief among these: a software bill of materials.

SBOMs must be:

- Machine-readable: It can’t just be a PDF or a table pasted into a Word doc. The SBOM must be parseable by other tools.

- Comprehensive: It must include all software components, their versions, and their origin (e.g., an open source or proprietary vendor).

- Informative: The SBOM must include support status and end-of-life dates for each component.

That last point is crucial. It’s not enough to list what’s in your device. The FDA requires details on component support, end-of-life status, known vulnerabilities, and your remediation plan. Consider:

- Which components are still supported by vendors?

- Which components are approaching end-of-life?

- Are there known vulnerabilities in any of these components?

- How will you remediate or mitigate risks?

2. Documenting Software Anomalies

2025 FDA guidance in “Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Quality System Considerations and Content of Premarket Submissions” further recommends listing known software anomalies and evaluating each for safety, exploitability, and proposed mitigations — a critical bridge between inventory and real-world risk. For each anomaly, manufacturers should evaluate:

- How it might impact device safety and effectiveness

- The likelihood of the anomaly being exploited

- The mitigations or controls in place

This is important because it connects directly to SBOM data. An SBOM might tell you what components you have — but anomaly reporting helps tie that inventory to real-world risks.

3. SBOMs Beyond Regulatory Filing

FDA guidance is clear: SBOMs are more than regulatory paperwork. Manufacturers are urged to share SBOMs with hospitals, clinics, and healthcare delivery organizations.

When critical vulnerabilities arise, such as Log4Shell, hospitals need to quickly assess whether affected devices are in use, the patient risk, and the remediation plan. SBOMs enable a faster, smarter response. Without them, hospitals can’t answer those questions quickly, which delays critical incident response.

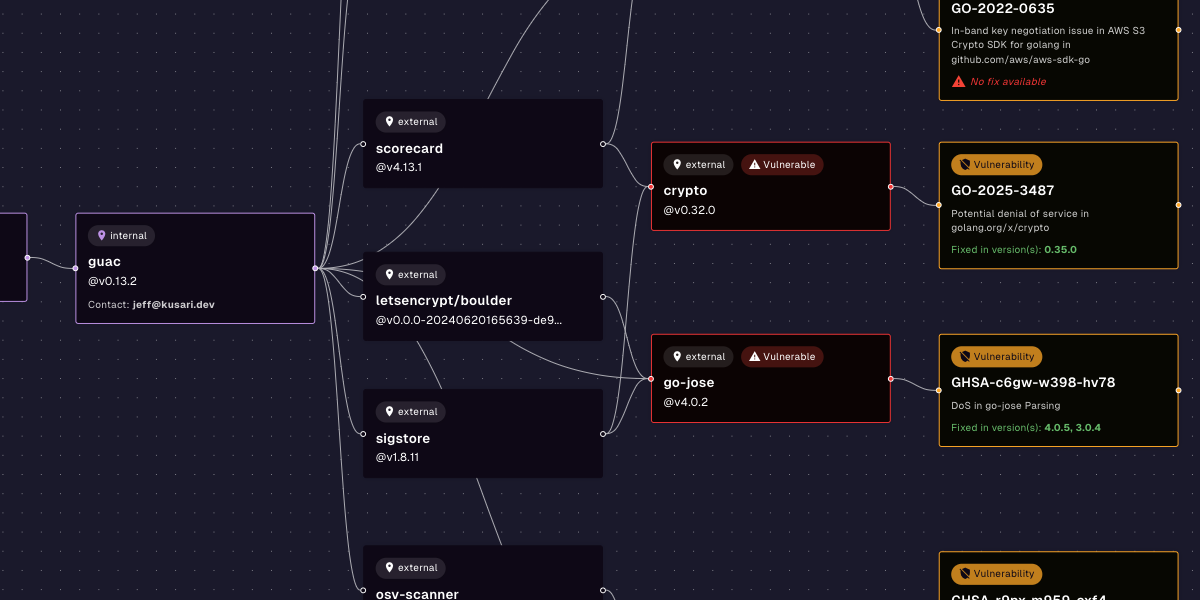

SBOMs Start the Journey

An SBOM alone is not enough to solve cybersecurity issues. You need SBOMs plus another data point to take action. For example, SBOMs plus CVE data will tell you what vulnerabilities you might be exposed to. SBOMs plus CVE data plus VEX data will tell you what vulnerabilities you’re actually exposed to. SBOMs help give you this information, but SBOMs alone don’t give you actionable insight.

Making SBOMs useful requires:

- Processes and defined procedures for reviewing SBOMs, identifying risks, and deciding mitigation steps.

- Tools that can parse SBOMs, map them with vulnerability databases (like the National Vulnerability Database), and assess exposure.

- Skilled professionals who understand how to evaluate risk in the context of medical device safety, regulatory obligations, and business operations.

Practical Questions SBOMs Should Help You Answer

For medical device manufacturers, and for the regulatory teams evaluating devices, SBOMs should help answer critical questions like:

- What vulnerabilities exist in current components?

- How severe are those vulnerabilities?

- Are any components unsupported or nearing end-of-life?

- Are vulnerabilities actively being exploited?

- Could any flaw impact patient safety or essential functions?

- Who’s responsible for remediation—and what’s the timeline?

- How will we communicate risks to regulators and healthcare partners?

This is where SBOMs become more than a regulatory checkbox. They become a tool for proactive risk management.

Proactive Risk Management: The New Imperative

Historically, many device manufacturers operated under the belief that cybersecurity could be handled reactively:

- Patch vulnerabilities as they appear.

- Respond to incidents when they happen.

- Deal with recalls only if regulators demand it.

That’s no longer viable. Reactive cybersecurity and post-market patching are no longer enough. The FDA now considers device safety inseparable from cybersecurity.

And if you’re in Quality, Regulatory, or Compliance roles, this means:

- You need to be involved earlier in the development lifecycle.

- You need clear visibility into the software supply chain.

- You need documented evidence that you understand your devices’ software risks and have a plan to manage them.

The Business Perspective: Why This Matters Beyond Compliance

Here’s another reason SBOMs matter and it goes beyond FDA requirements: business risk. A device recall due to a cybersecurity vulnerability isn’t just a regulatory problem. It can:

- Damage your company’s reputation.

- Cost millions in remediation and lost sales.

- Delay regulatory approvals for other products.

- Create liability exposure if patients are harmed.

Hospitals and buyers increasingly require SBOMs during procurement, making strong cybersecurity practices key to competitiveness and business success.

From Static Documents to Actionable Intelligence

Kusari is building solutions to transform static SBOMs into dynamic, actionable intelligence, standardizing machine-readable records, automating threat correlation, and rapidly sharing risk insights across the ecosystem.

The ultimate goal is to have an ecosystem where:

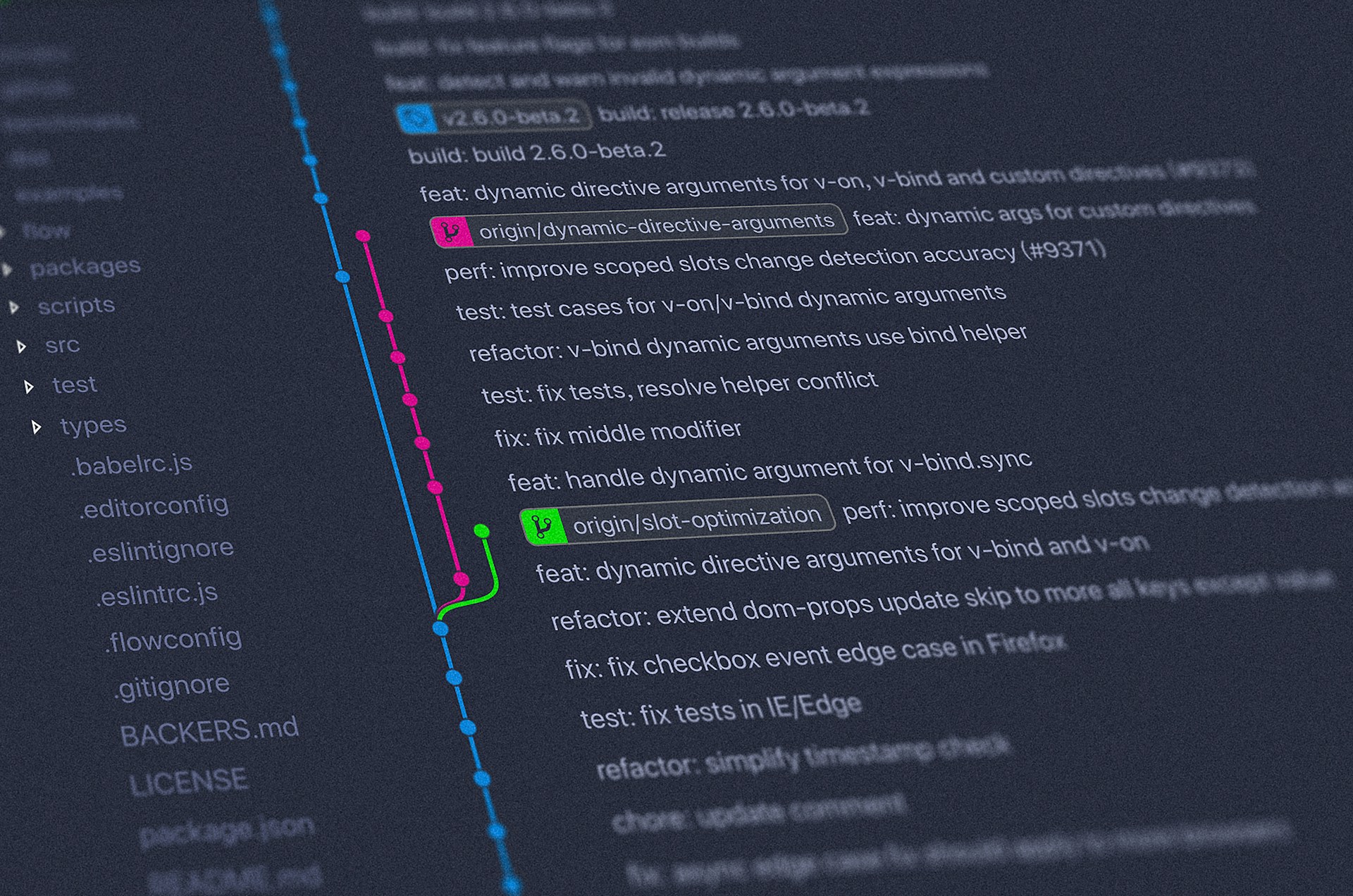

- SBOMs are generated automatically as part of the software build process.

- They’re machine-readable and standardized.

- They’re continuously correlated with vulnerability intelligence.

- Risk insights are shared quickly with regulators, partners, and customers.

So that, above all, medical devices remain safe for patients.

Advice for Medical Device Manufacturers

If you’re working in Software Quality, Risk & Compliance, or Regulatory Affairs at a medical device company, here are my top five next steps:

- Accept that SBOMs are here to stay. Even if the rules shift slightly, regulatory momentum is only increasing.

- Invest in automation. Generating and maintaining SBOMs manually is painful and error-prone. Automate it with a tool like Kusari Inspector as part of your build and release process.

- Don’t treat SBOMs as “just paperwork.” Use them proactively to identify risks, improve your security posture, and reduce surprises during regulatory reviews.

- Get cross-functional alignment. SBOMs touch engineering, security, regulatory, and legal teams. Make sure everyone understands their role.

- Be prepared to share. Hospitals and regulators increasingly expect transparency. Build processes that let you share SBOM insights safely and efficiently.

If you’re wrestling with the next steps for SBOM generation, medical device cybersecurity, cybercompliance, and supply chain risk management, connect with me on LinkedIn or contact us. Kusari is committed to turning SBOMs into living intelligence. We can help you implement security by design and know what’s in your device’s software so your organization is resilient and your devices are safer for patients.

Previous

No older posts

Next

No newer posts

.webp)

.webp)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)